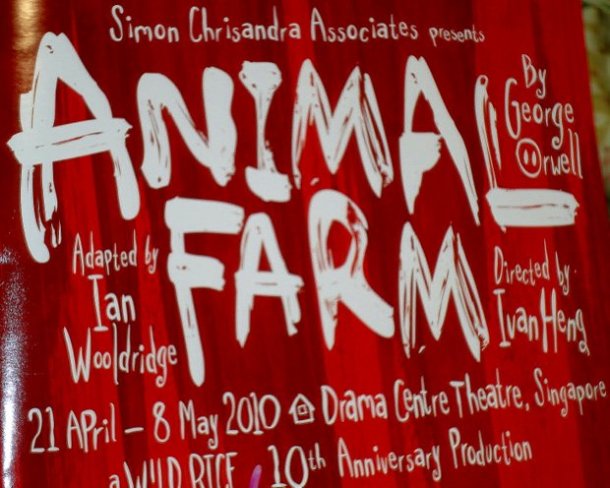

Ivan Heng’s 2003 restaging of George Orwell’s classic is wonderfully thought-provoking

IT’S BEEN AGES since I last read Animal Farm, undoubtedly one of George Orwell’s best-known works. So it was a pleasure indeed to be reacquainted with this timeless allegory – “A Fairy Story,” Orwell called it – through Wild Rice’s production of Ian Wooldridge’s faithful stage adaptation, for an appreciative Singapore audience in September 2003.

Singaporean theater prodigy Ivan Heng

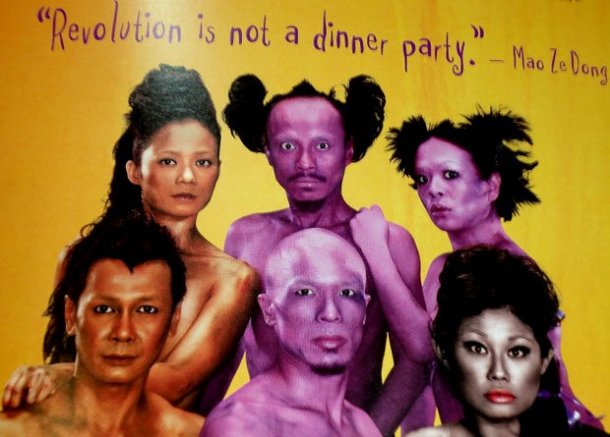

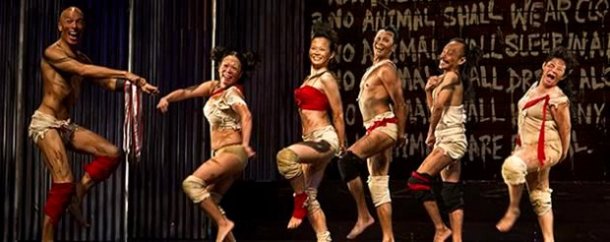

Directed by the immensely gifted Ivan Heng, Animal Farm impressed with the caliber of the performers, the quirkiness of the set, the artful make-up, and Philip Tan’s animated live music (a performance in itself). Heng opted for an unexpectedly sober and only slightly zany dramatization of the plot.

Relying largely on stylized movements and a very disciplined cast, Heng’s directorial vision was reminiscent of the “3D effect” of computer-generated animation (e.g., the Dreamworks production of A Bug’s Life in which the characterizations blur all boundaries between cartoon and realism). With well-defined physical mannerisms, the actors effectively created vivid animal personas that somehow made them human without anthropomorphizing them.

Lim Yu-Beng and Selena Tan were convincingly horsey as Boxer and Mollie, steadfast but a bit slow on the uptake. Ivan Heng, Gene Sha Rudyn, and Pam Oei were pricelessly piggish as Napoleon, Snowball and Squealer. As the ruthlessly ousted deputy, Sha Rudyn’s Anwarish goatee harked back to Leon Trotsky – and he was equally brilliant as Benjamin the literate but phlegmatic donkey, and cockily comical as the resident rooster. Michael Ian Corbidge’s Farmer Jones was a John Bullish political cartoon down to his Union Jack underpants, and he also doubled as Pilkington – a cross between Uncle Sam and a redneck evangelist entrepreneur. The casting of ruddy-faced angmoh Corbidge as Jones was an oblique allusion to our colonial past – a political subtext that wasn’t lost on the audience. When Napoleon harangues the animals and asks querulously if they want Farmer Jones to return and reclaim Manor Farm, it sounds like the sort of dire warning against the dangers of globalization you might hear at any Umno General Assembly.

Lim Yu-Beng and Selena Tan were convincingly horsey as Boxer and Mollie, steadfast but a bit slow on the uptake. Ivan Heng, Gene Sha Rudyn, and Pam Oei were pricelessly piggish as Napoleon, Snowball and Squealer. As the ruthlessly ousted deputy, Sha Rudyn’s Anwarish goatee harked back to Leon Trotsky – and he was equally brilliant as Benjamin the literate but phlegmatic donkey, and cockily comical as the resident rooster. Michael Ian Corbidge’s Farmer Jones was a John Bullish political cartoon down to his Union Jack underpants, and he also doubled as Pilkington – a cross between Uncle Sam and a redneck evangelist entrepreneur. The casting of ruddy-faced angmoh Corbidge as Jones was an oblique allusion to our colonial past – a political subtext that wasn’t lost on the audience. When Napoleon harangues the animals and asks querulously if they want Farmer Jones to return and reclaim Manor Farm, it sounds like the sort of dire warning against the dangers of globalization you might hear at any Umno General Assembly.

Ivan Heng’s Napoleon was a masterful study of a charismatic leader’s steady metamorphosis into demiurgic despotism. The political scapegoating of his erstwhile deputy into Public Enemy No. 1, leading to inquisitorial witch-hunts and party purges to divert attention from gross mismanagement, were chillingly, goosebumpily real – as Heng pigged out completely on his juicy rôle without ever succumbing to the temptation to “ham” it up.

As agitprop chief Squealer, Pam Oei’s high-pitched stridency evoked eerie memories of China’s cultural revolution when party cadres in Mao suits brandished copies of the little Red book at all potential dissidents and heretics. But hysterical Squealers are found in every ministry of “information.”

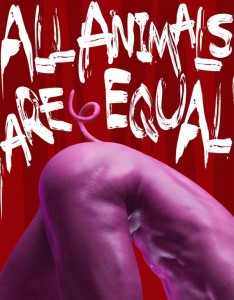

Audience participation consisted of our being invited to recite the post-colonial doctrine of “Four legs good, two legs baaaaaaaaaaaad!” in appropriately sheeplike tones. Indeed, since the only farm animals not represented on stage were the sheep, it fell to the audience to take on that rôle like good law-abiding, tax-paying citizens. For our valiant efforts we were paid off in sponsored pre-election apples.

Audience participation consisted of our being invited to recite the post-colonial doctrine of “Four legs good, two legs baaaaaaaaaaaad!” in appropriately sheeplike tones. Indeed, since the only farm animals not represented on stage were the sheep, it fell to the audience to take on that rôle like good law-abiding, tax-paying citizens. For our valiant efforts we were paid off in sponsored pre-election apples.

But with changing realities – and lucrative joint ventures signed between the porcine farm management and Pilkington the American corporate representative – leaflets had to be dropped from the rafters in four languages (English, Tamil, Malay and Chinese) proclaiming the new-era ideology of four-legs-good-two-legs-better. Another “Farm Development Project” to serve the needs of progressive animals, brought to us by Napoleon, the fine upstanding porker in a well-cut dark suit and red tie – standard uniform of the nefarious Illuminati World Management Team sported by NWO executives and their political proxies on all important occasions.

What Ivan Heng has achieved through this hip and savvy re-staging of Animal Farm with a distinctly ASEAN flavor is a revitalization of Orwell’s classic study of the neo-feudal mechanics of political power, giving it a fresh, contemporary sheen, rich in local color.

The somber theme of bad times getting worse is dynamically offset by very physical performances, and the insertion of a garish, carnivalesque grand finale – abetted throughout by the vigorous live music – mostly percussive – provided by an enormously exuberant and talented Philip Tan: he performs offstage for the most part, though visibly, but occasionally leaps onstage and contributes to the surrealistic mayhem. Air-conditioning ducts feature prominently as multi-purpose stage props, representing the pseudo-mystical fascination of newfangled technology – as well as the animal butcher’s van in which Boxer is carted off for slaughter when he outlives his usefulness to the System.

The somber theme of bad times getting worse is dynamically offset by very physical performances, and the insertion of a garish, carnivalesque grand finale – abetted throughout by the vigorous live music – mostly percussive – provided by an enormously exuberant and talented Philip Tan: he performs offstage for the most part, though visibly, but occasionally leaps onstage and contributes to the surrealistic mayhem. Air-conditioning ducts feature prominently as multi-purpose stage props, representing the pseudo-mystical fascination of newfangled technology – as well as the animal butcher’s van in which Boxer is carted off for slaughter when he outlives his usefulness to the System.

In short, Wild Rice’s Animal Farm was a totally credible – and more than creditable – tribute to George Orwell’s acute insight into the ploys and pitfalls of political power, and his dystopian view of the human condition. The production has been invited to tour New Zealand in early 2004 – and, hopefully, Malaysian audiences will get to see it soon after that. [Note: Ivan Heng’s Animal Farm was successfully staged in New Zealand, Tasmania, Hong Kong, and restaged in Singapore – but it still hasn’t happened in Malaysia, although in August 2017 a Malay version titled Kandang, directed by Omar Ali, is to be staged at KLPAC].

Ivan Heng’s first staging of Animal Farm in 2002 earned him the DBS-Life Theatre Award for Best Director. In his director’s notes for the souped-up 2003 version, Heng states: “This production was a gut reaction to the ‘War against Terror’ in Iraq. I remember sitting in front of the television on March 20th, feeling sick to the core as I watched the first bombs on Iraq fall. If there is one thing I’m learning, it is how Governments can become so separate from the very people who vote them into power. Watching the news made me think about how the media has the power to distort and manipulate the truth. It made me think about my responsibility as an artist. If only to understand my personal response to the events of the world, I was searching for a way of expressing my confusion and disappointment.”

“In the world of Animal Farm, most speechifying and public palaver is bullshit and instigated lying, and though many characters are good-hearted and mean well, they can be frightened into closing their eyes to what’s really going on.” – Margaret Atwood

George Orwell @ Eric Blair

BORN ERIC ARTHUR BLAIR on June 25, 1903 in Bengal, George Orwell’s centennial in 2003 stirred up some controversy about the validity of his status as a literary icon, with leftwing critics bristling over the fact that Animal Farm had been co-opted as an antisocialist tract by rightwing interests.

His detractors have remarked on Orwell-Blair’s long history of hobnobbing with the secret police – as a police officer in Burma, BBC propagandist for India and Southeast Asia, and British Intelligence consultant on anti-communist strategies during the early days of the Cold War. Whose side was he on? Was he in truth the maverick Winston Smith or master manipulator O’Brien (two key characters in 1984) – or was he perhaps both?

Some of the sharpest minds are recruited for psyops (psychological warfare) and Eric Blair just happened to have an acute literary flair – and a profound loathing for the cynical mass-control mechanisms installed by the ruling elite to perpetuate its feudalistic stranglehold on the human imagination. Upon leaving Burma he embraced anarchism with a vengeance, and then swung to the extreme left, fighting fascism in the Spanish Civil War. Then he got disenchanted by the communist movement and chose the life of a penniless vagabond for several years – an experience that spawned his first book, Down and Out in Paris and London (1933), and later The Road to Wigan Pier (1937).

The soul’s yearning for freedom is doomed to futility in Orwell’s universe, and one gets the sense that he finally gives up fighting the Status Quo because he can see no way out: it’s a task he finds morally repugnant, but he will serve the Dark Lords of the Matrix by inserting himself into 10 Downing Street as a future prime minister – not as an Orwell, of course, but as a Blair – in any case, as someone supremely fluent in Doublethink and Newspeak.

The soul’s yearning for freedom is doomed to futility in Orwell’s universe, and one gets the sense that he finally gives up fighting the Status Quo because he can see no way out: it’s a task he finds morally repugnant, but he will serve the Dark Lords of the Matrix by inserting himself into 10 Downing Street as a future prime minister – not as an Orwell, of course, but as a Blair – in any case, as someone supremely fluent in Doublethink and Newspeak.

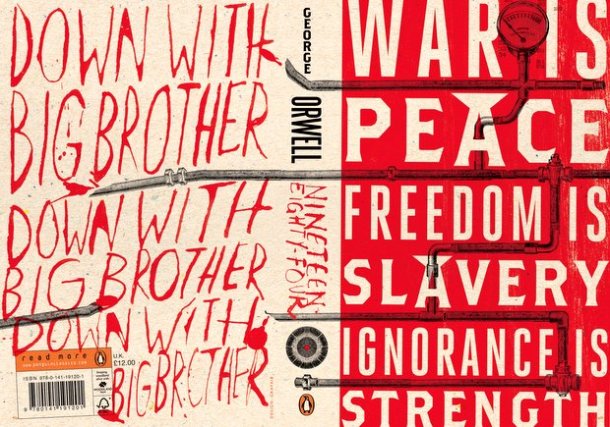

Therein lies the poignant irony of Orwell’s dark, visionary novels – especially 1984 (written in 1948) which is a perfect prescription for a Big Brother power elite ruling through sloganeering, disinformation and public relations – and when all that fails, ruthless police brutality. Precisely the sort of world we find ourselves living in today, where war is peace and might is right, and history an infinitely rewritable cut-and-paste business.

Winston Smith, the chief protagonist of 1984, is turned around by the mind control experts in Room 101 where, confronted by his deepest, darkest fears, his rebellious individualism is broken – and the novel concludes bleakly with the socially rehabilitated citizen Smith drinking Victory gin at the local and watching Big Brother on the boob tube along with all the other faceless plebes – while the chorus of a popular ditty echoes in his brain: “Under the spreading chestnut tree/I sold you and you sold me.”

But Orwell’s intellectual integrity and his extraordinary skill as a writer more than redeem his own internal conflicts – and his readers are left with the onus to seek, and ultimately find, a non-polarized resolution beyond the dire straits of divide-and-rule dualism.

25 November 2003