Antares very nearly nods off at Lee Swee Keong’s Nyoba Dance+ offering

Call me an old stick-in-the-mud, but I’m one of those diehard conservatives who generally hopes to gain some pleasure, joy, insight, epiphany, revelation, or even simple amusement from an evening at the theater. All I gleaned from A Cherry Bludgeoned, A Spirit Crushed was that the Chinese avant-garde has hit the big time in KL – and that there’s a horde of young dancers, musicians, designers, and actors with enormous energy, ego-drive and talent – but with no sense of direction or purpose other than to get their efforts known beyond the confines of their own circles. These are post cari makan Chinese in search of greater makna (meaning) – or, perhaps, unmakna!

Well and good, you might say, but at what point does an artist’s need for attention become an impudent imposition on his or her audience? Again, the age-old question: where do you draw the line between the arty and the merely farty? The answer is really quite simple: when you leave the theater feeling robbed of your time, rather than privileged to have witnessed something beautiful and true. No doubt there were a few in the audience who derived a great deal more meaning from the performance than I did – if only because they could understand the metaphorical or mythical context of what struck me as a visually mesmerizing but utterly obscure bit of mummery – with only some Chinese subtitles to go by and a smattering of Cantonese and Mandarin verbiage thrown in. Not much help really. And the program was equally obscure. True, there was a repetitive poetic commentary in English very seductively read by Merissa Teh – but the words fully matched the choreography in terms of obscurity: “ah! fawn of youth!/dapper/stalwart/thick of thigh/well equipped/bandit advances/my dagger at the draw/just in case...”

Okay, that takes us back to a recent production of Rashomon in which Lee Swee Keong played the monk, and very credibly too. Merissa Teh’s sultry voice reinforced the impression that Lee had found his basic inspiration from the famous Japanese saga of rape (after all, wasn’t it Merissa who played the ravaged wife?)

What about the projected kinetic text? Ah, that came right out of Hiroshi Koike’s Spring In Kuala Lumpur – another production in which Lee shone – as did the dangling cucumber in lieu of a dead sparrow (but why not a carrot? I guess cucumbers are much easier to disembowel).

What about the Ikea tealight-lit cooking sequence with gas stove, garlic and cooking oil? Aha! Lee must have really liked Aida Redza’s Tiga Naga, which had the dancers pounding sambal belacan in stone mortars and swallowing the spicy shrimp paste to produce dragon’s breath.

The performers comprised Ian Yang, Caecar Chong, Kiea Kuan Nam, Lee Swee Keong – and a chimeric horse on castors which was led round and round the stage for no less than 15 minutes (it was at that point I found myself nodding off) while techno-composer Goh Lee Kwang played DJ with a trance-inducing rhythmic loop on his laptop.

Initially emerging clad only in yellow briefs, the dancers wasted no time transforming themselves into Chinese court ladies in black, red, yellow and blue – thereby surpassing Joe Hasham’s Importance of Being Earnest by attempting the cross-dressing right on stage. Costume designer Khoon Hooi must have had fun dressing the horse.

In any case the “love horse” – the most evocative element in the entire production, with its otherworldly antlered head conjuring images of Cernunnos the ancient forest deity or mystic unicorns – came in handy as an excuse for audience participation. People were invited on stage to mount it and be photographed just before the finale.

Goh’s electronic music succeeded in generating a hypnotic ambience, though it lacked the subtlety, texture and lyricism attained by dancer-composer Weijun Loh’s recent audio experiments. It’s no great feat to create a nerve-racking cacophony that merely drains the audience’s energy. Fortunately there were enough funky bits to make up for the headache-inducing intro – but I must remark at this juncture that plagiarising from Ravel’s Bolero without due acknowledgment or credit may well constitute an artistic offence. But I suppose Maurice is long dead and can’t object too much.

Mac Chan’s lighting was, as usual, one of the more redeemingly competent elements of the production and contributed greatly to the arty atmosphere rather than the farty. The same cannot be said, alas, for Lau Mun Leng’s performance art or live installation, as the program describes it. While the “ladies” are busy preparing their “meal” on stage, Lau is busy scrawling cryptic numbers and energy lines around them and finishes up by wheeling onstage a blood red toilet bowl overflowing with foam and decorating the foam with fake bloodstains. Now what was that supposed to represent? That the moon was exerting her periodic influence on the court ladies? Or was it merely an idea borrowed from Paul Loosley’s madcap staging of Ubu Roi last year in which toilet bowls were the leitmotif? I hope the director wasn’t insinuating that his artistic vision was crap!

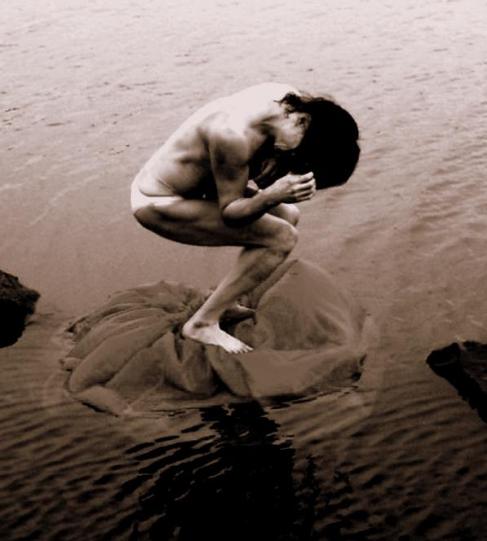

I have long been an admirer of Lee Swee Keong’s work as a dancer-performer. He has invariably impressed with his focus and technical skill – primarily as a butoh exponent with Lena Ang’s feisty dance company (which unfortunately vanished from sight when she got married and emigrated, though she left Lee her artistic legacy). Indeed, the butoh influence remains clearly visible in Lee’s overall approach to movement, hence the stately, lethargic, zombiesque choreography. Lee is undoubtedly of shamanic (or perhaps extraterrestrial) lineage and has the power to draw attention – even adulation and awe – upon himself like any true magician.

However, magic has the power to liberate or entrap. On the cover of the souvenir program, the production was ingenuously described as “a scintillating gem by Lee Swee Keong.” Was that tongue-in-cheek? I don’t think so. As I picked up my tickets for the show I glanced at the poster and read a glowing endorsement by someone named Wish Teo… or was it Wishful Teo? Can paying audiences in Malaysia sue for misleading advertising, I wonder?

In the case of A Cherry Bludgeoned, A Spirit Crushed, what ended up bludgeoned was my patience; and what ended up crushed were my hopes for an inspiring, stimulating, and enjoyable evening. A copy-and-paste collage of vaguely artistic postures does not the cutting edge in dance theater make.

1 December 2003

[Color images courtesy of Kelvin Tan]