Antares pigs out over Jit Murad’s SPILT GRAVY ON RICE

Good home cooking imparts a marvelous sense of well-being. Who was it who defined patriotism as a fond memory of all the wonderful things we tasted in our childhood?Well, that makes Jit Murad a true patriot and an even truer playwright. Simply because he has a knack of serving up some timely home truths without ever sounding pedantic or preachy, and his brilliant agility with words makes a long story seem short and sweet. Through the rich and spicy stew of human melodrama generated by just one genetic hodgepodge of a family, Jit brings the story of modern Malaysia up to date with sagely wit and deep compassion.

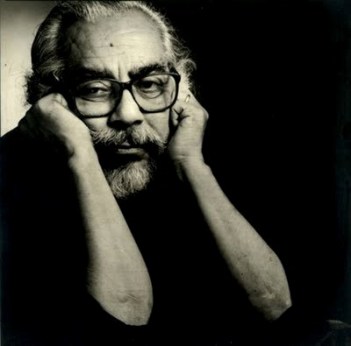

Dato’ Rahim Razali as Bapak

His unapologetically polygamous Bapak – impressively portrayed by the highly durable Dato’ Rahim Razali – redeems the image of the patriarch as progenitor, our father on earth. Which is no easy feat considering the boorish, bullying shadow side of the Bapak figure that dominates our political history. In the gentlest possible voice, the playwright derides a wawasan without otak – a national vision with little intelligence or soul. His allusion to the abysmal events of May 13, 1969 – which have for decades marred the national psyche and perpetrated the unhappy ethos of aggressive denial (and the compulsive dishonesty it breeds) – was handled with incredible grace and tenderness. At a time when the nation is confronted with the imminent departure of an overbearing and all-powerful Bapak, the play resonates on more levels than can be grasped with one viewing. And yet, Jit’s astute observations transcend the pettiness of politics and attain the sublime heights of a humane social philosophy that heals old wounds and reconciles apparent contradictions.

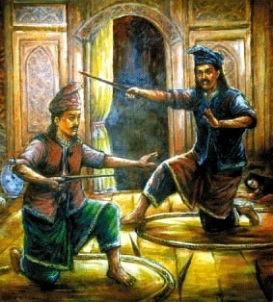

Sean Ghazi as Husni

Bapak’s five children (actually six, all from different mothers) represent a cross-section of the educated class: Zakaria is a rake (“You mean he’s the black sheep of the family?” “No, more like the black goat!”) whose rebellion against his father’s value system makes him a cynical opportunist (which he blames on his piratic ancestry); Kalsom is a controversial (read attention-craving) dramaturge and poet totally engrossed with her own artistic ambitions; Darwis, a frustrated academic turned literary critic and family biographer; Husni, a successful architect and closet gay; and Zaiton, a typical aspiring Toh Puan ensnared in the comfortable complacency of the haute bourgeoisie. Bapak has a few more tricks up his sleeve, but it’s not for me to reveal them here.

Bernice Chauly as Kalsom

While the casting was astute, the performances were slightly uneven. Reza Zainal Abidin and Sean Ghazi were absolutely spot on as Darwis and Husni. Elaine Pedley was an utter delight as the winsome Willow Gomez (“an over-enthusiastic interpretative dancer”) who also stood in as the memory of all the women in Bapak’s life. Benjy and Eijat were excellent as Azri and Michelle (Husni’s gay lover and Zakaria’s transvestite friend), and Ahmad Ramzani Ramli wholly credible as Kalsom’s faithful assistant (and worshiper).

Soefira Jaafar’s affected interpretation of Zaiton was not altogether convincing, but we may attribute that to her relative inexperience as an actor. Bernie Chan, making her acting debut, was elegantly entertaining as Hortense Chia, Zaiton’s confidante and childhood friend. Bernice Chauly looked really smashing as Kalsom and so did Charon Mokhzani as Zakaria – but their long absence from the boards made them a wee bit self-conscious in the early scenes, although both evidently possess thespian skills aplenty. One hopes their return to the limelight will stir up the adrenaline sufficiently for them to get hooked all over again.

Raja Maliq, set designer

It’s an exciting venture indeed to be part of the creation of an original play and the entire cast and crew deserve a mighty round of applause for the wonderful energy they invested in bringing Jit Murad’s fourth (and most mature) full-length play to life. Mac Chan’s lighting was precise and efficient; and Raja Maliq’s set design, which resembled a giant closet, rather ingenious, though the thin plywood construction seemed somewhat wobbly. The well crafted sound by Wong Pek Fui was, on the night I caught the performance, miscued a couple of times by an inexperienced operator – but that was perhaps the only amateurish touch in an otherwise commendable first staging of a complex dramatic work. The material is so engagingly textured that it can be interpreted in endless ways, and it’s almost certain that Spilt Gravy On Rice will see many more incarnations in years to come and in places yet undreamed of.

Director Zahim Albakri has molded, with loving attention and intuitive aplomb, Jit Murad’s delectable text into a nourishing, soul-satisfying theatrical experience. Rise, Sir Jit and Sir Zahim, and receive your well-earned accolades and hugs.

Oh, by the way, look out for a couple of unnamed characters (Men In White) whose surprise cameo appearance alone is worth risking an evening out in the permanent haze of KL.

2003